This past week in my Construction Management class we have been discussing project management, and specifically project delivery systems. This prompted me to begin thinking about what the architect’s responsibilities are in the construction process. Specifically, I am wondering if it is the architect’s responsibility to make both architecture and construction a more transparent process to consumers. This question came into focus even more upon my reading of chapter one of Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets by Barry B. Lepatner. Although his book is about how to fix the construction industry from an economic point of view by providing owners with more information up front in order to reduce the excess cost and time of many modern day construction projects, I had many ideas about how the industry standard processes of how an owner procures a project could be changed.

HOW ARE BUILDINGS BUILT: PROJECT DELIVERY SYSTEMS

I think that the adversarial relationship between architects and contractors arises from these industry standard project delivery systems, along with others. Although many projects look very different and seem to have varying levels of complexity on the design side, in the construction industry they are mainly procured (that is “built” by the owner) in one of four major ways, and merely need scaled up. I have diagrammed and briefly explained these delivery systems below:

The most popular construction process today and for the past century or more is that of “design-bid-build”. In this method of building procurement, the owner and its partners propose a program for the project to meet their business objectives. The owner must have prepared a plan for the building which will allow for it to match their present and future needs to the site. They also must know how much they can afford to spend on the project and the timetable by which it must be completed.

After the owner has defined what they would like to have these desires are relayed to the architect who then interprets them into a design and, subsequently, drawings. Sometimes, the architect or owner will hire additional consultants for specific aspects of the design of the building (i.e. engineers, interior designers, etc.) to help develop a complete solution.

When the design is nearing its ending stages the owner invites General Contractors (GC’s) to bid on the drawings and other specifications, called construction documents. When the GC bids on these documents they assume they are 100% complete, which is usually not the case (leading to many change orders that can increase the original bid amount later on). Upon winning the bid, a contract is awarded and construction begins. It is at this point that the GC “buys out” all subcontracted work and proceeds with the project.

Once construction begins, the GC is responsible for coordinating and scheduling the work. “It is during this “build” phase that conflicts, errors, and omissions are discovered in the design team’s bid documents, unforeseen and concealed site conditions are uncovered, and myriad other minor and major derailments encountered” (Lepatner). These problems result in change orders from the GC which must be approved by the owner and, often, the architect.

“Architects often contend that complete, fully coordinated sets of plans are not possible on large, complex projects [which I don’t believe is true with modern BIM software like Revit and Navisworks]. They assert that the fast-track process chose by owners ad construction managers precludes this from occurring. Almost always, contractors find that changes in the design during construction are necessary to actually get the thing built.”

Because of this, it is not suprising that, although working together to accomplish the same goal in theory – producing a building – because the architect and construction team are not traditionally working together from the beginning to ensure a practical and constructable design it is no wonder then that architects and Construction teams have typically had an adversarial, if not combative, relationship.

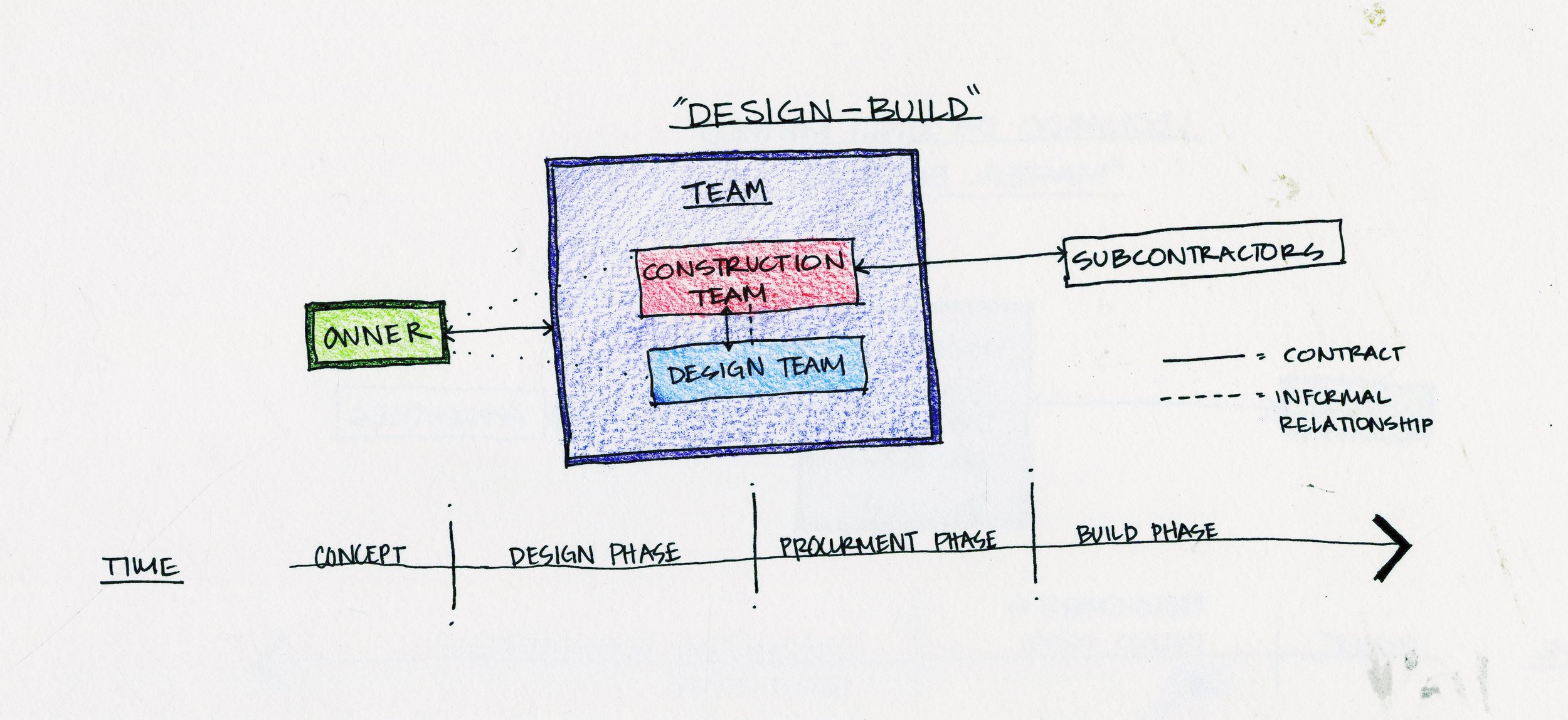

An increasingly popular project delivery system is design-build. In this process the design team and construction team are combined into a joint entity, with contractors typically leading the team and hiring design professionals or entering into a joint venture with the design firm. Although there are fewer disputes from the contractor when utilizing this method, the designer is typically restricted, even from the conceptual stages by cost and ease of construction concerns. In this way they are essentially nothing more than an “architect of record” for the project, providing their stamp on standard plans that the construction company is used to working with. Because of this many off the shelf solutions are used, and many of these projects become very un-interesting, standard, or “cookie-cutter”.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARCHITECTURE AND CONSTRUCTION

As I have begun meeting and working with more and more people in the construction program I have gained a new respect for the field, a respect that I believe many of my peers in architecture are lacking. Before I began this program I, like many other architecture students I have spoken to, didn’t understand the difference between construction management and trade work. I classified everyone in both fields as “construction workers” and, partly because of my experiences with the industry, had a very prejudiced view of these people as big, gruff, burly men with hardhats and big boots, sweaty, swearing and standing around hardly working. We, as architects “know” that they don’t care what the final project looks like, as long as they are home by 5 with a check in their pockets. We are taught that if we don’t specify exactly what we want, quality will suffer at their hands.

This opinion could not be further from the truth.

“The men and women working in this industry … work within an industry that time has forgotten. The way we build today differs little from how our ancestors built churches and sphinxes hundreds and thousands of years ago. No one denies it. Everyone would prefer to do better.”

I think these prejudices arise from the fact that the construction process is not explained to us very well in school. Learning the bare minimum of construction techniques, which is mostly trade work, we are taught to view architecture as a sacred act of design and many famous architects as just a step down from god. This leads to an extreme lack of knowledge about the construction process as a whole, but especially as it relates to costs of various parts, assemblies, and scope of work. And we have little to no sense of the time it takes to complete the building of the things we design. In short we have almost no comprehension of how our building is actually BUILT.

In analyzing the relationship between architecture and the act of building, I think it is important to remember how each field views the concepts of drawing and building. In architecture drawing is thought of as a verb, while buildings are viewed as nouns. Quite the opposite in construction, drawings are thought of as objects, while building is the action. This is an important distinction to make because this fundamental difference is where many of the problems arise.

HOW TO FIX THESE PROBLEMS

I dont pretend to have all the solutions… yet. However, in my next post I plan to outline some of my ideas about how this relationship, and the architect’s role in the construction process, could be improved.