Stage of Construction: Completed

Contact: Dave Dryden, DC Dryden LLC, Project Manager

Type of Construction: Worship and Classroom Spaces Converted from an old Big Box Retail Store

Estimated at: $7 million

I had a special connection to the site of my first site visit. As a child, my dad was the landlord of the property and during a long period between owners I was, almost daily, riding my bike inside through the big open spaces, exploring the behind the scenes of the mezzanine and secret rooms and finding old stuff that had been left behind by people while my dad was doing maintenance work.

Seeing the site today was shocking to say the least. Although not an active construction site (the keys were handed over a couple months ago) I was able to walk through the entire project with the project manager who oversaw the whole production from start to finish. He also gave me an entire set of architectural and civil drawings for the project.

There were a few unique things about the construction process of the building that I would like to point out:

Cassions, in this case called helicals, and shaped like screws had to be placed in many parts of the building to reinforce the structure for the new use because of poor soil bearing capacity. The most suprising area for me was that 61 were required under the main stage in the sanctuary, each about 14” in diameter each!

Also to reinforce the existing structure they had to move columns and shore up existing concrete cassions to receive the extra load.

There were no fire stop walls in the entire porject. So, in response to that there is excessive firproofing EVERYWHERE.

An Audio Visual Consultant was not included in the GC’s scope of work but everything else, including finishes was performed by subcontractors of the GC, for which Dave Dryden was a consultant and performed the position of Project Manager and Superintendent.

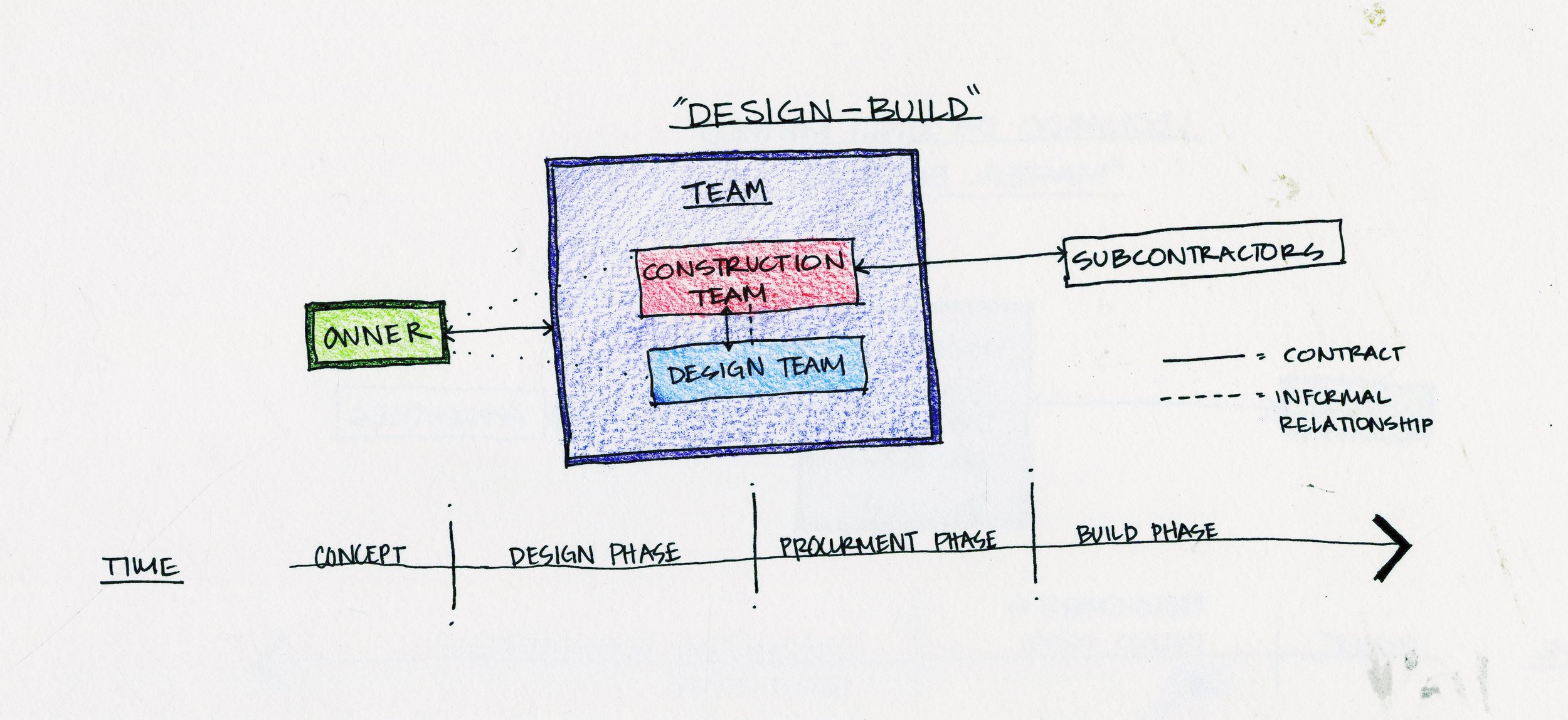

This was a Design-Build project. There was no bidding process, but rather the contract was awarded to a friend of the owner.

I thought it was imporeesive that, because so much of the existing slab had to be ripped up to do various plumbing and structural work, they brough machinery into the building through temporary garage-style doors installed in the front facade.

Dave and I spoke alot about the way in which he scheduled the building process. He mentally split the building into two halves- along grid line G. He then further seperated that into 6 areas, proceeding clockwise around the building except for the sanctuary which was the final space, area 6. ((DIAGRAM))

Additionally, there were concepts and terms that I learned from this job that I hadn’t hear of before:

- Attic Stock (specified by architect)- required in the contract, an extra supply of various building and finish materials (ex. Flooring tiles) so that owner can perform maintinenece. Specified as a percentage of total needs for the job of each material.

- RFI’s = request for information for architect and how those relate to PCOs (potential change orders)

- Acclimating stock and materials and allowing time for that in the schedule- this will prevent warping, settling too much

- Occupancy Permit- can be granted by the city once all parts of the project related to life safety are complete (i.e. floors don’t necessarily have to be down yet but fire suppression systems have to be in place) allows the owner to start moving in.